Germane Cognitive Load

Because your brain learns best... when it doesn't get all the answers

Your brain absorbs language most effectively when it needs to make its own connections, not just receive translations. Purposefully designed conversations that don't reveal everything encourage you to guess, connect, and create your own meaning. Germane Cognitive Load explains how this effort helps the brain build permanent knowledge structures, just like young children do by listening and interpreting repeatedly. Research shows that “just right” difficulty and “understandable ambiguity” lead to sustainable language learning — language isn't taught, it's constructed inside our minds.

True language learning isn’t about memorisation

Cognitive Load Theory

Neuroscience reveals that the brain truly “learns” only when it puts in mental effort to build its own understanding — this is called “germane cognitive load.” This concept comes from Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988), which divides the brain's mental workload into three types:

- Intrinsic Load – The inherent difficulty of content, such as Japanese pronunciation being harder than English.

- Extraneous Load – Unhelpful or excess effort, like confusing explanations or an overloaded interface.

- Germane Load – Productive effort, when you work to build understanding, such as linking new words to contexts you’ve seen before.

When we allow our brains to think, analyse, and connect ideas for ourselves, we create “schemas” — internal models of understanding. That’s the true process of learning.

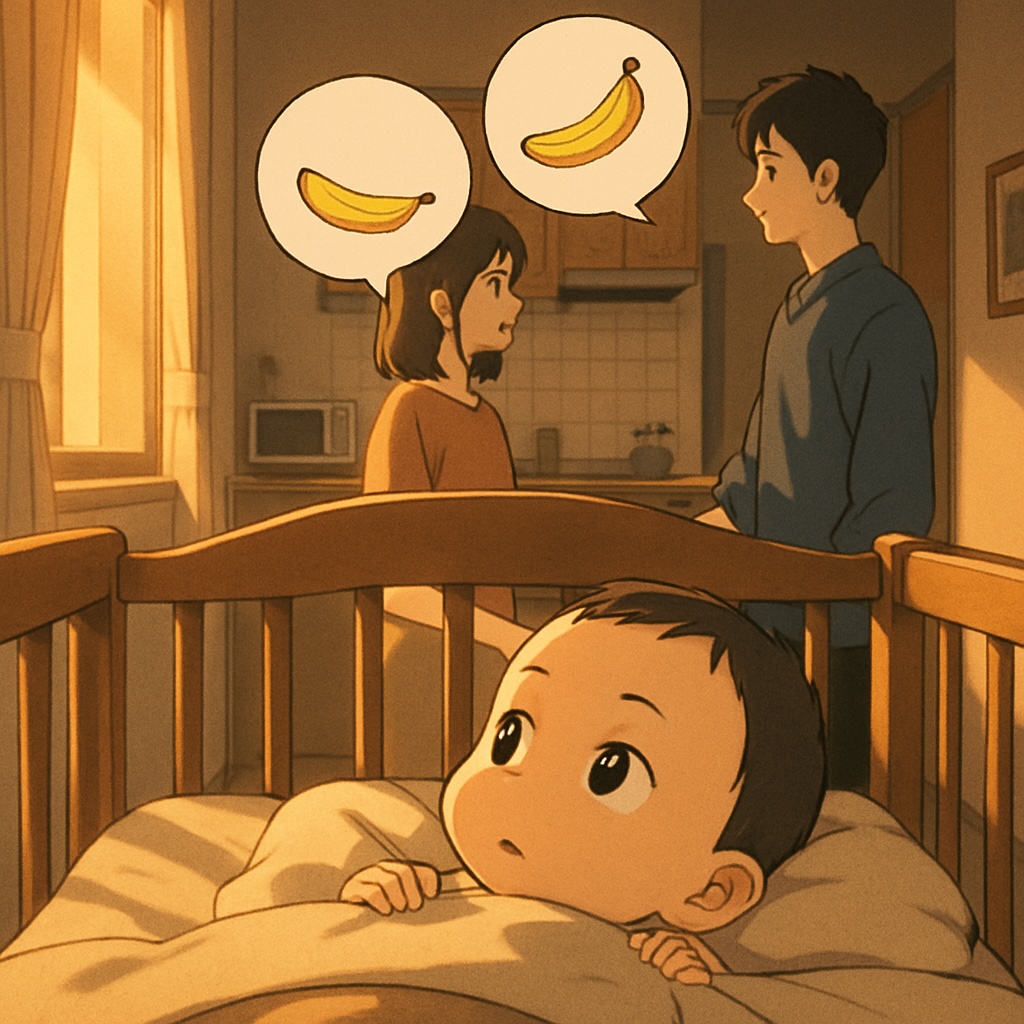

Young children acquire language naturally this way

Patricia Kuhl’s research (University of Washington) shows that babies as young as 6–12 months use statistical learning — they listen to repeated sounds and unconsciously detect sound patterns. For example, after hearing “banana” repeated, a baby learns it’s one word, not just three syllables. Children learn from real contexts, not translations. When a parent says 'let's eat' while holding a spoon, the child links the sound “eat” with 'food' and a warm feeling. Understanding doesn’t come instantly; instead, the brain gradually pieces together meaning from repeated experience. This is a natural process of building germane load.

“Desirable Difficulty” – The right level of challenge helps your brain grow

Robert Bjork (UCLA) describes this as Desirable Difficulty: our brains learn most effectively when the challenge level is “just right”:

- Too easy → The brain doesn’t need to think

- Too hard → It gives up

- Just right → The brain puts in the effort to build new understanding

That’s why real language learning doesn’t give you every answer — it creates the right amount of challenge, encouraging your brain to make sense of things and strengthening neural connections (synaptic strengthening) and neuroplasticity in the process.

The science behind Germane Cognitive Load

Here’s a sample language-learning dialogue:

👧 “昨日、映画を見たよ。”

きのう、えいがをみたよ。

kinō, eiga o mita yo.

🧒 “へえ、誰と?”

へえ、だれと?

hē, dare to?

👧 “友だちと。とても楽しかった!”

ともだちと。とてもたのしかった!

tomodachi to. totemo tanoshikatta!

In this example, the app doesn’t reveal all word meanings immediately — for instance, 昨日 (きのう / kinō — yesterday) or 楽しかった (たのしかった / tanoshikatta — had a great time). Learners can infer their meanings from clues about “movies” and “friends” and the story being shared.

This makes your brain:

• Connect the context → Guess meaning

• Notice verb patterns → Like “〜た” to indicate past tense

• And the more you encounter the pattern, the deeper your understanding grows.

This is how children learn from birth — but here it’s designed to fit adults, making your learning faster and more efficient.

Nick Ellis (University of Michigan) found that manageable ambiguity helps the brain use Bayesian inference — drawing inferences and adjusting understanding from context. A hint of ambiguity becomes fuel for thinking. When learners have to 'guess' from context, your brain is actively engaged, working like a scientist to arrive at the best explanation. The end result is active learning — your brain creates its own understanding, not just passively receiving answers.

With AI able to answer anything in an instant, it’s easy to let it think for us — but this reduces germane cognitive load. MIT researchers found that users of large language models (like ChatGPT) show significantly lower EEG activity than those who think and write on their own. In language learning, AI should act as a “thinking partner” (Cognitive Coach), not just an “automatic dictionary.” For example: - AI can ask: “What do you think this word means in this context?” - Or give feedback precisely when you’re unsure. These strategies help maintain germane load so your brain continues to actively work.

Humans learn language best when they:

- Hear real input in context

- Interpret it themselves

- Get helpful feedback

- Repeat the process in new situations

Children repeat this process thousands of times before uttering their first words. Adults can too, but with tech designed to “provoke thinking” instead of “hand over all the answers.” True language learning isn’t about memorising vocabulary, but training your brain to “interpret, connect and make smarter guesses” — just as you did before you ever spoke your first word.

References:

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science.

- Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings.

- Kuhl, P. K. (2004). Early language acquisition: Cracking the speech code. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

- Ellis, N. C. (2002). Frequency effects in language processing: A review with implications for theories of implicit and explicit language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition.

- MIT Media Lab (2025). Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt (preprint).